The unmet needs of addiction

Denise Winn: journalist, editor, therapist and author.

This article, originally published in Healthcare Counselling and Psychotherapy Journal, Denise Winn describes how the human givens approach to addiction focuses on identifying not only the client’s unmet needs but also the barriers to their fulfilment.

Carola was desperate to get her binge drinking under control. She proudly told me that she had managed to stop drinking alcohol five years previously, ending years of misuse. But every few months or so she would go on a bender and binge drink. It could take her a month or more to get back on track – and she wanted help.

I congratulated her on managing to change her drinking behaviour so successfully. I also asked her what was happening around the times she would binge drink. She shrugged, not having thought about this before. ‘Going to some sort of celebration, I suppose, and getting carried away.’ I was doubtful that was the real trigger and, when we dug deeper, it was clear that she went to a lot of celebrations where she could manage quite comfortably not to drink.

Carola thought harder. ‘Maybe I associate it with feeling angry about something and then thinking: Oh, blow it! I’m going to have a drink.’ But when we investigated further, anger didn’t seem to be the common factor either. She could recall many occasions when she had felt really angry and had not resorted to drink. I invited her to focus for a moment on that feeling of deciding to let rip on alcohol in a defiant sort of way, to see if the circumstances around the first time it happened might float into her mind.

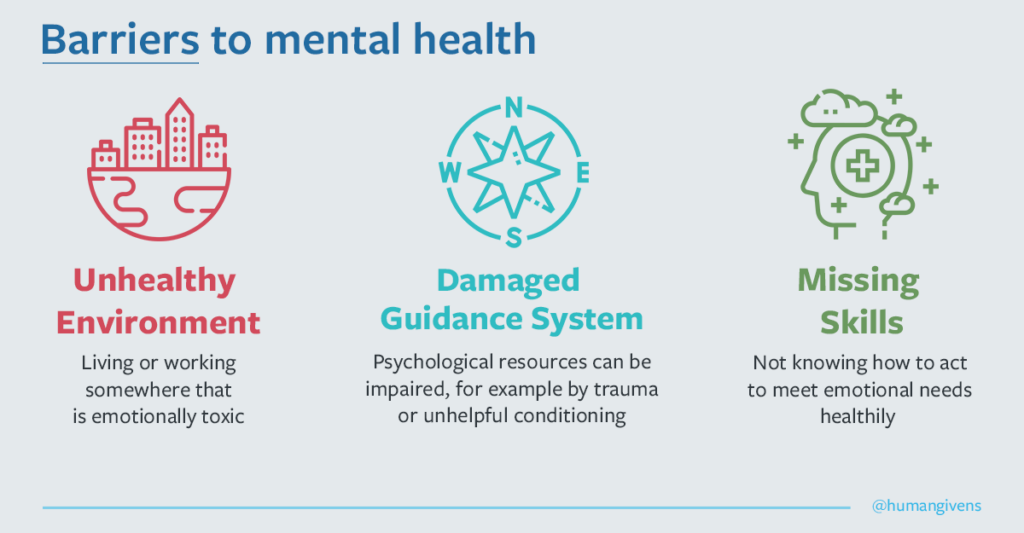

The human givens approach to therapy is based on the understanding that we not only have essential physical needs but also essential emotional needs, as well as innate psychological resources to help us meet them. Problems with mental health, such as stress, depression, anxiety, anger, addiction or even psychosis, occur when needs are not adequately met or resources are inadvertently misused or damaged. Many things can block us from getting our needs met in a healthy way. Co-founders of the human givens approach, Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrrell, have identified the three major barriers:

- living in a toxic environment, whether an abusive home, an unsafe neighbourhood, a bullying workplace or surrounded by pollutants that make us sick

- inability to use our innate resources well enough because of damage, such as trauma, unhelpful conditioning or insufficient physical nourishment

- misusing coping skills – people might unwittingly misuse their innate resources, or might never have learned important relationship or emotional management skills.¹

When our needs are not well met, we are most at risk of engaging in unhealthy activities, which appear to bring relief or satisfaction but can become addictive. So, people might turn to drink or drugs to blot out pain, or to pornography, online gambling, retail therapy and comfort eating to make up for a lack of intimacy, connection or sense of achievement. Of course, if they are to continue to deliver any satisfaction, addictive activities have to be regularly ramped up – and can eventually get out of control.²

‘Problems with mental health… occur when needs are not adequately met’’

For a human givens practitioner, the work is about identifying unmet needs and addressing the barriers. In Carola’s case, she had suffered a traumatic reaction to the shock of being cruelly disrespected, which flooded through her whenever she found herself in roughly similar circumstances. The reaction stopped her from thinking clearly, leaving her defences down and ready to revert to the remedy she had adopted the first time: drinking to oblivion.

In human givens parlance, we call this ‘pattern matching’ (neuroscience has since identified the same phenomenon as prediction).³ So, associated reactions resurface before judgment or rational thinking gets a look in, until the pattern can be broken.

Rewind technique

When appropriate, human givens practitioners use a refined version of the rewind detraumatisation technique to break such patterns.⁴ It involves deeply relaxing the client and guiding them backwards and forwards through a ‘film’ of a selection of the traumatic events that fit the pattern. Without the inhibiting effect of high emotional arousal, the relevant networks of the brain can recognise that a traumatic incident is in the past and can be safely ‘filed away’, instead of re-emerging as a continuing threat.

I used this technique with Carola, to break the association with the first time she drank to excess to block out the blow to her self-esteem – and we included the most vivid and unsettling of the subsequent occasions, when she felt she had disgraced herself by binge drinking. Of course, we then needed to enable her to regain her confidence in herself and to find more effective ways to handle any perceived unkind assaults on her character – in other words, to teach her new skills.

Coping skills

Teaching coping skills is an important part of the work carried out at the Bayberry residential clinics in Oxfordshire, Warwickshire and the West Midlands. The clinics use the human givens approach in their hugely successful work with clients who are struggling with seriously disordered substance abuse and other addictions and obsessions. Having detoxed and/or detraumatised clients, teaching coping skills comes next. During therapy with Niall, a shy young man with a serious drug problem, it emerged that he had absorbed from social media that he should be ready to have sex on first dates and perform like a stallion, both of which he felt uncomfortable about. So, in order to ‘provide the sex’, as he put it, he would get himself high. He also had a poor body image, so used drugs to feel more confident.

‘What he was missing was the knowledge that, in a loving relationship, where people feel safe, supported and respected, minor flaws that people perceive within themselves are loved, even if perceived as flaws,’ says Bayberry CEO and senior psychotherapist Mandy Cooper. ‘I asked him to think of the oldest happy couple he knew and to consider their wrinkled skin, grey hair or balding heads, liver spots, scars and other age-related imperfections. Did they display disgust and rejection of one another?

‘Reframed in that way, Niall could recognise that the drug use was just a side effect of his misunderstanding, not the primary issue. Just stopping the drugs wouldn’t have resolved a thing. We had to reframe his view of relationships.’⁵

The human givens way of working with addiction is respectful. It focuses on what is not working in people’s lives (because of barriers to the meeting of needs or the unintentional misuse of innate resources), not on their symptoms and shortcomings. It can therefore change the way that people with serious addiction difficulties view themselves, eliminating the self-loathing that can often stand in the way of accepting or engaging with treatment.

‘People might turn to drink or drugs to blot out pain’

In her account of this story, Mandy Cooper points out that it’s not uncommon for clients to believe they are at fault for their condition and don’t deserve compassion. Indeed, in many in-patient addiction treatment settings, the self-blame is inadvertently strengthened by policies such as removing phones or requiring people publicly to share their shame or to apologise/make amends to those they might have hurt through their behaviour.⁵

The patterns that become embedded and lead to addiction are, of course, extremely potent. An essential element in therapeutic work with addiction for a human givens practitioner is the instilling of healthy, even more powerful patterns to facilitate a change of behaviour and attitudes.

Counter conditioning

Human givens practitioners are taught a highly effective ‘counter-conditioning’ method, which involves the client making informed choices while in a relaxed state during guided imagery – a powerful component of the process, and a skill that all practitioners learn. Deep relaxation induces trance, a suggestible state, in which, through guided imagery tailored to the individual, more empowering understandings can be absorbed and adopted.⁶

I remember working this way with Judith, a bubbly but timid woman of nearly 60, referred to me by a charity. Judith drank when she needed courage. As a result, her family had largely disowned her, even though the emotionally abusive behaviour of her then husband was the main cause of her loss of self-confidence.

Judith didn’t like to go out much, but her granddaughter was shortly to be christened and, to her joy, she had been invited to the christening. But Judith would have to get on a coach by herself and travel out of town. We worked successfully on breathing techniques to keep her calm. When she was relaxed, Judith also visualised herself making her way keenly to the coach station and sitting comfortably on the coach, using the calming techniques we had practised to deal with any setbacks or withdrawal panics.

Judith wanted to appear strong and confident at the christening, because her family had always dismissed her as a little mouse. When I asked what animal represented her hidden qualities, she immediately said: ‘A lioness.’ So, we used the image of a lioness to build her sense of her own strength and to help her manage any anxiety about seeing her ex-husband – the person who had first made her feel like a mouse – and wanting a drink to quell the feelings.

The christening went off successfully and, as our sessions progressed, Judith continued to gain confidence in other areas of her life, interacting with people more and engaging in activities. When our sessions finished, more of her needs were being met and her drinking was under her control.

Sometimes, inducing relaxation in a conventional way is not possible. For example, when I counselled heavy substance abusers living in hostel accommodation, relaxation was impossible, because it meant relaxation of vigilance and, on the street, that could lead to getting robbed, urinated on or beaten up. Even in the hostel, there was a constant fear of theft that caused many residents to stay hyper-alert. So, it’s important to be versatile and able to apply various methods for changing patterns.

Storytelling

For instance, human givens practitioners can achieve a lot through storytelling, which is another means of putting people into a trance. An appropriate story told at the right time can have a big impact. The story of Odysseus ordering his men to lash him to the mast of his ship in order to stand firm against the call of the sirens has much to communicate at an unconscious level about choosing to overcome addiction.

‘Human givens practitioners use a refined version of the rewind technique’

A significant proportion of the charity’s clients have serious addiction problems, alongside many other difficulties, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from war zone experiences, often involving moral injury. Many symptoms of PTSD impair ability to function, which affects family relationships.

People with PTSD are also often quick to feel and act with anger, a pathological reaction, exacerbated by the rapid violent responses legitimately required in combat situations. But it can lead to family breakdown, homelessness, inability to find work, arrests for violent or criminal behaviour and prison sentences.

‘Teaching coping skills is an important part of the work’

Some veterans can even develop an addiction to picking physical fights they know they will lose. The injuries and pain they suffer in the process act as a temporary means of suppressing their trauma memories.

There is also a growing awareness of complex PTSD among veterans, as emotionally unstable, chaotic or frightening upbringings can provide a catalyst for joining up. But when they leave or are discharged from the armed forces, the stability and routine they found are lost – and they might lack the coping skills to forge a different life for themselves.

Addressing trauma

Nevertheless, it is still common for veterans to be told by mental health services and charities that they must be ‘clean’ before they can access help. PTSD Resolution is different: if a client can turn up to a session in a fit state to engage, the charity will help. Usually, the work starts with tackling the trauma, which the veteran is using the substance to mask. Once that has been dealt with, the addiction and unhelpful life strategies can be addressed in the usual human givens manner. It is telling that Op Courage, a nationwide veterans’ NHS mental health service, refers clients to PTSD Resolution.

A study by researchers at King’s College London, published in 2025, which used the NICE real-world evidence recommendations to compare PTSD Resolution’s outcomes with those achieved within IAPT services (now known as NHS Talking Therapies), showed that PTSD Resolution had a much higher acceptability and far lower dropout rate. Overall, 82% of PTSD Resolution’s clients completed the therapy successfully, compared with just 55% of those in IAPT, attending two sessions or more.⁸

Overcoming an addiction is one thing; maintaining abstinence is another. As with most programmes for dealing with addiction, built into the human givens approach are strategies to maintain abstinence from addictive activities.

The strategies include recognising triggers, drawing up a plan to deal with them and accepting the possibility of the occasional setback, all of which can be embedded effectively within guided imagery – a vital adjunct in enabling our clients to rehearse coping behaviours in a safe situation and to grow confident about success.

In my view, the human givens way of working is satisfying to deliver and helps our clients meet more than one of their crucial needs: a sense of autonomy, facilitating self-respect, self-belief and a corresponding sense of achievement.

Human Givens College runs accredited CPD workshops on addiction, guided visualisation, rewind and storytelling in London, Bristol and Leeds, as well as online training on moral injury, trauma and addiction. Information about the in-person workshops can be found at www.humangivens.com/college and the online course on addiction at www.humangivens.com/treating-addiction

Human Givens College

References

1. Griffin J, Tyrrell I. Human givens: an empowering approach to emotional health and clear thinking. East Sussex: HG Publishing; 2024.

2. Griffin J, Tyrrell I. Freedom from addiction: the secret behind successful addiction busting. East Sussex: HG Publishing; 2005.

3. Barrett FL. How emotions are made: the secret life of the brain. London: Pan Macmillan; 2017.

4. Winn D. Rewinding trauma. Therapy Today 2025; 36(3): 30–32.

5. Cooper M. Overcoming addiction with compassion – and no stigma. Human Givens 2023; 30(1): 16–21.

6. Winn D. Shifting perspectives. Therapy Today 2024; 35(1): 26–28.

7. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Real-world evidence framework. www.nice.org.uk/corporate/ecd9 (accessed September 2025).

8. Hall CE, Greenberg N. A service evaluation of PTSD Resolution therapy for military veterans. Occupational Medicine 2025; 75(2): 105–112.